Supposedly dropped food is safe for about five seconds. Is there any truth to this supposed "rule"?

I dropped a piece of chocolate the other day, and briefly wondered just how many bacteria I had added to my tasty treat. But I saw no dirt, so went ahead and popped the chocolate into my mouth.

After all, my kitchen floor is pretty clean and the chocolate had been on the ground for less than five seconds.

The "five second rule" was therefore in my favour, obviously. We all know that rule, right? Any food picked up from the floor is perfectly fine to eat within five seconds of dropping it.

But was I right to eat it, or had I unwittingly stuffed my mouth full of tiny, harmful microbes?

We asked you, our trusty BBC Earth community, what you would do in a similar situation.

The rule must be true, says Adam Harmsworth. "Surely all bacteria and infectious organisms understand the concept of time," he says.

Wishful thinking Adam. Gary Burch says that he goes by a three-second rule but for another reason entirely. "That's the average time from when I drop food on the floor until the dog has finished eating it."

There is not a swarm of bacteria lying on the ground, waiting to pounce on any food that comes their way

Manuel Rodriguez says that he is a poor grad student, so he follows the five-minute rule. But others are far stricter. Corinne Howard says: "If it doesn't go straight to mouth it goes in the bin."

"We're talking about microseconds for bacteria to reach your just-dropped food," says Jon Bedet. "A zero-second rule would make more sense."

It "depends on the food and how hungry you are," says Lane Jasper.

To settle the debate, I put the question to scientists who specialise in microbes. Would they eat dropped toast, or pizza, or for that matter, dropped sticky toffee?

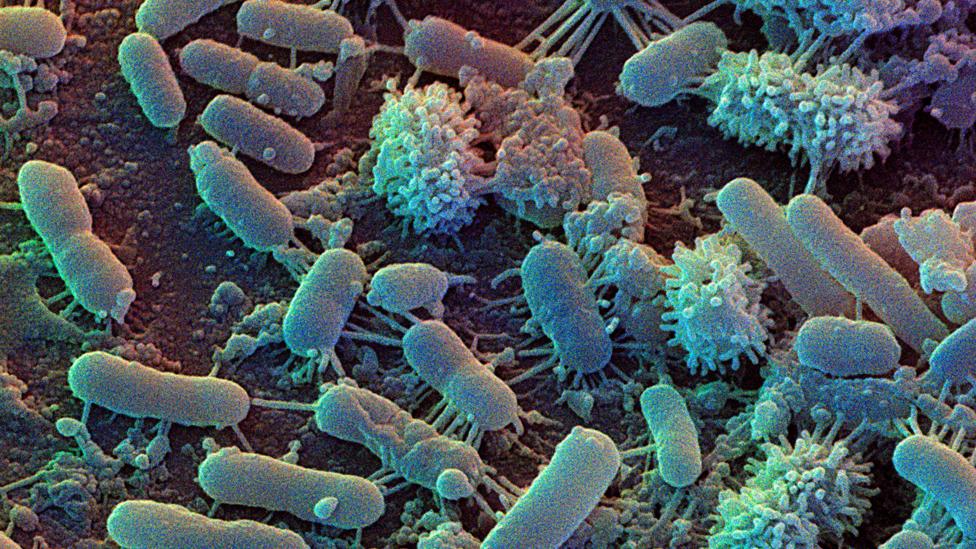

First of all let's get some facts straight. There is not a swarm of bacteria lying on the ground, waiting to pounce on any food that comes their way.

You are literally living and breathing a sea of bacteria

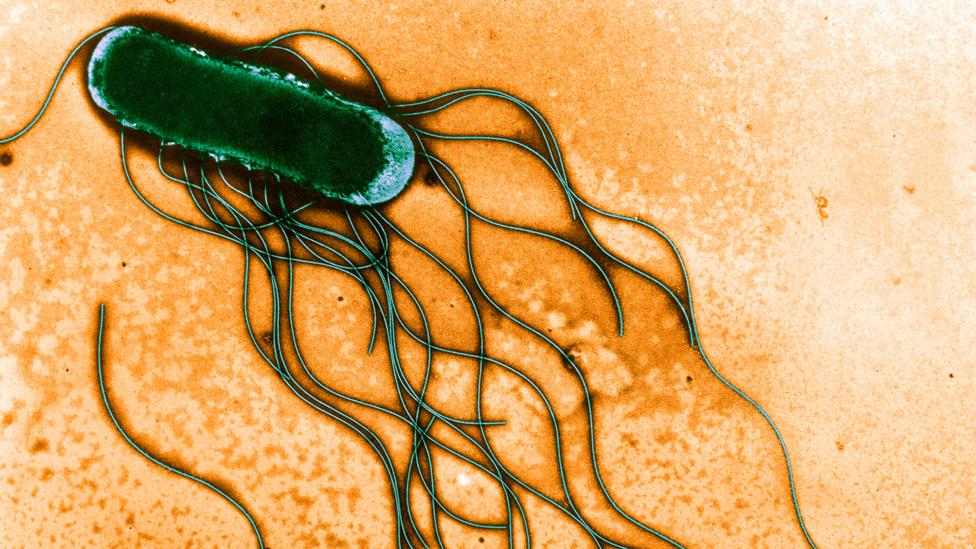

Instead, they are already everywhere, even if you have just mopped the floor. Adam Taylorhelpfully points out: "Scientifically speaking there is no five-second rule. If the food touches surface for nanosecond it is contaminated."

As soon as any food touches the floor, "of course it will pick up 'dirt'", and therefore microbes inside that dirt, says Jack Gilbert, a microbial ecologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois, US.

At any one time, there are about 9,000 different species of microscopic creatures lurking in the dust in our homes, including 7,000 different bacteria, according to a 2015 study. Most of them are harmless.

They are all over you all the time; on your hands and face, and in your house. We are constantly shedding bacteria through our skin and through the air we breathe.

"You can't hide yourself from microorganisms. That's the whole point. You are literally living and breathing a sea of bacteria," says Gilbert.

If I dropped it into a plague pit, no, I wouldn't pick it up

Researchers have even put a figure on it. Each person emits about 38 million bacterial cells into their environment each hour, a study found.

And yet, says Gilbert, we have been told for over 100 years that microorganisms are dangerous and "we need to kill them all".

"We are so paranoid about dirt and yet we have no comprehension of the pure luck – or bad luck – that it takes to actually pick up a pathogen," he says.

Gilbert would certainly eat food that he drops, provided the environment was reasonably safe. "If I dropped it into a plague pit, no, I wouldn't pick it up," he clarifies.

In fact, he goes further. Most of the time, even licking your floor or your toilet seat is unlikely to make you sick.

However, it would not be wise to do so if someone in your household is sick or if you are in a country with poor hygiene records.

There is no magical barrier between yourself and the bacterial world

There are certainly some harmful pathogens around. But if one is lurking on your floor, it could also be elsewhere in your house, perhaps on your kitchen counter or door handle. You could become ill regardless of whether you ate food from the floor.

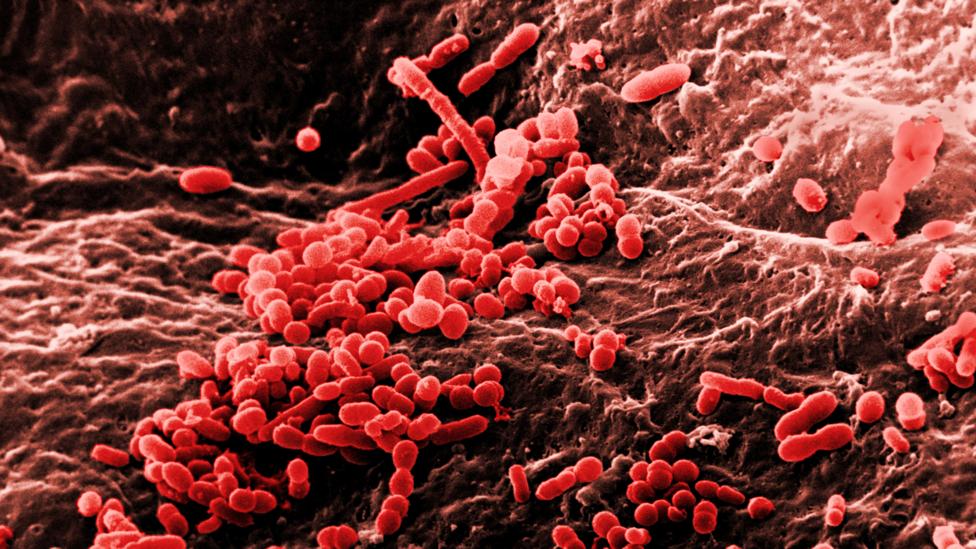

The usual warnings apply. If you are unlucky enough to hostSalmonella bacteria on your floor, dropped food could make you sick even if it was on the ground for five seconds or less.

One 2006 study found that there was less risk of exposure ofSalmonella in five seconds than one minute, but the risk was still there.

There is no magical barrier between yourself and the bacterial world, so even the strictest cleanliness will not keep them out.

In fact, contact with the microbial world can benefit us.

If there really is a nasty microbe about, sticking to the rule is not going to prevent you from getting sick

"Unless you are dropping food in a doctor's office or in a portable toilet, exposure to microbes is good," saysKatherine Amato of Northwestern University in Illinois, US.

That is because we have evolved with microbes all around us. Researchers like Amato increasingly believe that they have played a significant role in the evolution of our species.

We pick up microbes from our environment when we are very young, including from contact with dirt. A child's "microbial community" starts to look like an adult's at around the age of two.

"If there are microbes on that piece of food it could [therefore] contribute to the development of the healthy immune system," says Amato. "I say go ahead and eat it."

"You don't build an immune system by being a germophobe," agrees Natalie Henning.

In other words, the five-second rule is nonsense. If there really is a nasty microbe about, sticking to the rule is not going to prevent you from getting sick. And the rest of the time, it is fine to eat food from the floor.

I'm not sure I want to try licking toilet seats, though.

Melissa Hogenboom is BBC Earth's feature writer. She is@melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

Follow BBC Earth on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter.

Disclaimer

All content is provided for general information only, and should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of your own doctor or any other health care professional. The BBC is not responsible or liable for any diagnosis made by a user based on the content of this site. The BBC is not liable for the contents of any external internet sites listed, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned or advised on any of the sites. Always consult your own GP if you're in any way concerned about your health.